Algorithmic Manipulation and Information Science: Media Theories and Cognitive Warfare in Strategic Communication

Article Main Content

This study examines the evolution of media theories within military communication, focusing on the interplay between traditional frameworks such as propaganda and framing theory and modern advancements like algorithmic manipulation and cognitive warfare. Through qualitative and comparative analyses, the research investigates how these theories have shaped public perception and strategic narratives during key military conflicts in Croatia and Europe over the past three decades. Leveraging advanced methodological tools, including Gephi and MAXQDA, the study visualizes the dynamics of information flows. It highlights the transformative role of digital technologies in amplifying polarizing narratives and fostering information dominance. By bridging traditional media strategies with modern algorithmic approaches, this research provides actionable insights for policymakers and military strategists, underscoring the critical need for regulatory frameworks to counter misinformation and algorithmic bias. The findings enrich an understanding of information warfare’s implications for public discourse, democratic institutions, and global security.

Introduction

The evolution of media theories is pivotal for understanding the intricate relationship between media, audiences, and society, as well as the influence of media on public opinion formation and the shaping of cultural norms (McCombs & Shaw, 1972; Weaver, 2007). Media theories serve as explanatory frameworks for understanding how media act as intermediaries between real-world events and their audiences. The development of theories such as the Agenda-Setting Theory, exemplified by the works of McCombs and Shaw, highlights how media do not explicitly tell audiences what to think but rather what to think about by emphasizing specific topics while downplaying others. This process shapes social reality and priorities within public discourse (McCombs & Shaw, 1972; Weaver, 2007).

Applying theoretical frameworks to analyze Croatia’s media system sheds light on critical factors, including political pressures, ownership structures, digital transformation, and media pluralism. Media in transitional societies like Croatia often navigate complex adjustments to new political and economic conditions. Media ownership significantly impacts the independence and pluralism of journalistic practices, particularly in transitional societies where democratic institutions are still evolving. Studies on Southeast European media systems emphasize these dynamics and their implications for public discourse (Jakubowicz & Sukosd, 2008; Londoet al., 2004). The concentration of media ownership directly impacts pluralism and independence, as evidenced by studies on Central and Eastern European media systems (Jakubowicz & Sukosd, 2008; Londoet al., 2004). Media theories provide a foundation for understanding their role in shaping societal realities and fostering democratic participation (Habermas, 1989). Splichal’s analysis underscores the role of public opinion as a mediator between media content and democratic involvement, emphasizing the evolution of public discourse in the twentieth century (Splichal, 2001). This study breaks new ground by employing advanced computational tools such as Gephi for network visualization and MAXQDA for qualitative analysis to bridge the gap between traditional theoretical frameworks and the demands of real-time information management in military and strategic communication contexts. For example, George Gerbner’s cultivation theory demonstrates how consistent exposure to specific content can shape audience perceptions of reality, mainly through television and digital media (Gerbner & Gross, 2017). This aligns with Bandura’s social learning theory, which emphasizes the role of media in shaping behaviors and beliefs through observed interactions (Bandura, 1977). Contemporary research extends this theory to new media technologies, exploring how spreading misinformation on social media can further cultivate erroneous perceptions of reality (Shin & Thorson, 2017).

These theories help explain why specific societal issues dominate public discourse in societies where media are central information sources. Recent studies illustrate how social media algorithms amplify the ‘filtering’ effect, determining what users see and how they interpret this information, ultimately influencing public opinion and creating “echo chambers” (Bakshyet al., 2015; Pariser, 2011).

With the rise of new technologies and digital platforms, new theories are required to understand how digital media influences traditional media, social relationships, and information consumption patterns. Theories of media convergence (Jenkins, 2006) and uses and gratifications (Sundar & Limperos, 2013) have adapted to digital environments, explaining how audiences interact with media in personalized ways and selecting content tailored to their preferences, including interactive digital media.

Moreover, media theories are essential for shaping laws and policies that regulate the media. Understanding the media’s role through theoretical frameworks assists legislators and regulators in making decisions that ensure media pluralism, freedom, and journalist protection. The propaganda model proposed by Chomsky and Herman (1989) highlights how media operations often align with elite interests, influencing policy outcomes (Herman & Chomsky, 2002). For instance, research on digital platform regulation and its impact on democracy has increasingly become a focus of academic and political debates (Gillespie, 2018). The development of media theories facilitates a more profound comprehension of media’s impact on society, public opinion, and political processes. On a global scale, information dominance and algorithmic manipulation have emerged as critical tools in geopolitical strategies (Bacevich, 2005). For instance, disinformation campaigns in the United States during the 2016 presidential elections leveraged social media algorithms to polarize voters. Similarly, in China, the ‘Great Firewall’ exemplifies how state-controlled information ecosystems enforce propaganda and suppress dissent, demonstrating parallels to European and Croatian experiences while emphasizing the unique integration of technology in these strategies (Herman & Chomsky, 1988).

The earliest development of media theories emerged in the first half of the 20th century when researchers and theorists began systematically studying the effects of mass media on society. These theories reflected the rapid growth and expansion of media platforms, including print media, radio, and later television. Katzet al. (2017) further expanded on these foundational ideas, emphasising the role of interpersonal communication in shaping media influence, mainly through opinion leaders and their impact on audience reception. The development of the media landscape and the theoretical frameworks that sought to explain its dynamics have evolved through history, aligning with changes in technology, social structures, and cultural patterns. Academic work and theoretical debates have been instrumental in formalizing these ideas, enabling the development of sophisticated analytical tools for studying media effects. Prominent theorists such as Harold Lasswell, Paul Lazarsfeld, Elihu Katz, George Gerbner, Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann, and Noam Chomsky have significantly contributed to understanding media and their role in social life. Their work identified key processes and mechanisms through which media influence public opinion and societal values and shaped academic discussions about media as an indispensable element of modern social systems. These theories and approaches, meticulously developed over decades, continue to serve as a foundation for further research and analyses in communication studies. In this context, it is essential to emphasize that theoretical contributions in media studies are not static but continuously adapt to new media technologies, social changes, and global cultural transformations.

Research Objectives, Questions and Hypotheses

Information science has undergone a significant transformation with the integration of digital technologies, profoundly impacting the realm of military communications. This research seeks to explore the dynamic relationship between media, algorithms, and public perception within the framework of information warfare. Investigating how algorithms and media manipulation shape strategic narratives contributes to a nuanced understanding of contemporary strategies for achieving information dominance, bridging theoretical exploration and practical implications (Bakshyet al., 2015; Hallin & Mancini, 2004). The central aim of this research is to examine the transformative role that digital technologies and algorithmic frameworks play in modern military communications. Specifically, the study identifies and analyzes dominant media theories applied in military contexts over the past three decades. It also evaluates the effects of algorithmic manipulation on public perception and assesses its implications for strategic communication in Croatia and the broader European landscape. Furthermore, the study contextualizes the role of information warfare in reshaping security paradigms within the digital era, positioning itself at the intersection of theoretical inquiry and applied strategy. This research is guided by critical questions that address the evolution of media theories in military contexts and their adaptation to the complexities of information warfare. Central to this inquiry is an exploration of algorithms’ role in influencing public perception and constructing narratives during military conflicts. Additionally, the study interrogates the comparative dynamics of information warfare in Croatia and other European nations over the past three decades, aiming to uncover patterns and unique characteristics shaped by distinct sociopolitical and historical contexts.

The research is anchored in the hypothesis that algorithmic manipulation of media content significantly shapes public opinion about military conflicts and security threats. It further posits that the evolution of media theories is closely linked to the growing complexity of information warfare in the digital age. Lastly, the study hypothesizes that Croatia’s media ecosystem exhibits distinct attributes in applying military media theories, influenced by its post-conflict sociopolitical environment and integration into European security frameworks. This articulation of objectives, guiding questions, and hypotheses establishes a clear foundation for the research, providing a coherent framework for the following methodological and analytical processes. By aligning the study’s aims with its theoretical underpinnings and practical applications, this section ensures that the research is rigorous and relevant within the broader discourse on media, communication, and military studies in the digital age.

Method

This research adopts a qualitative approach, focusing on analyzing the evolution of media theories in a military context, specifically applied to cases from Croatia and Europe over the past thirty years. The methodological foundation is based on content analysis, discourse analysis, and case studies, which provide a deeper understanding of the impact of media theories on information warfare and perception shaping. Content analysis was conducted using data collected from news archives, scientific databases, and official documents from national and international organizations. The focus was identifying key theoretical frameworks that have shaped the media space in the context of military operations and crises. Particular attention was given to propaganda, framing, and algorithmic manipulation theories, emphasizing their influence on strategic communication and public opinion formation. Discourse analysis facilitated the examination of linguistic and symbolic patterns used to construct narratives about military conflicts and security issues. The analysis explored how media manipulate information to achieve political and military objectives, including using rhetoric and visual elements that reinforce specific ideological messages. A case study approach was employed to contextualize the findings. The research analyzed the Croatian War of Independence, the annexation of Crimea, the conflict in Ukraine, and NATO’s intervention in Kosovo. These cases were selected due to their historical significance, information manipulation intensity, and relevance to understanding contemporary military communication strategies. The methodological framework was enriched by applying modern analytical tools that enable processing large volumes of data. Software such as MAXQDA was used for text analysis, while Gephi facilitated the visualization of network connections within information systems (Castells, 2011; Claverieet al., 2022). Monitoring the virality of disinformation on social media was conducted using algorithmic systems tailored for this purpose, further emphasizing the intersection of digital technologies and information warfare (Newmanet al., 2021). This aligns with broader trends in media consumption where digital news reports highlight the critical role of algorithmic amplification in shaping public opinion.

By incorporating a phenomenological approach, the research examined the subjective experiences of actors involved in informational processes (Ellul, 2021; Pomerantsev, 2014). This included the perspectives of journalists, military experts, and political stakeholders within the context of propaganda, cognitive warfare, and strategic communication. This methodology allowed for an in-depth exploration of the complex interdependencies between media, technology, and military operations, providing rich insights into contemporary communication strategies in the digital age. The use of MAXQDA for qualitative coding allowed for systematic analysis of themes such as algorithmic manipulation and public opinion shaping, while Gephi was instrumental in mapping information flows and interconnections between media platforms and actors. These tools enhanced the empirical rigor of the study and provided a strong foundation for the analytical insights presented in the results.

Results

The results are structured to directly address the research objectives and hypotheses, providing a clear trajectory from theoretical frameworks to empirical findings.

Evolution of Media Theories in Military Contexts

Historical and contemporary sources analysis identified key media theories applied in military contexts, including propaganda, framing theory, and algorithmic manipulation. Propaganda theory has historically dominated early conflicts, while modern conflicts have increasingly integrated algorithmic manipulation and digital framing. Table I summarizes the application of these theories across three case studies: the Croatian Homeland War, the annexation of Crimea, and NATO’s intervention in Kosovo.

| Theory | Application in Homeland war | Application in Crimea annexation | Application in Kosovo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Propaganda | High | Moderate | High |

| Framing theory | Moderate | High | High |

| Algorithmic manipulation | Low | High | Moderate |

Table I demonstrates the temporal and regional differences in the application of media theories, with algorithmic manipulation playing a central role in modern digital conflicts (Gerbner & Gross, 2017; Gillespie, 2018). The findings align with Gerbner’s cultivation theory and Pariser’s filter bubble hypothesis, showcasing the varying relevance of media theories in different military contexts.

Impact of Algorithmic Manipulation on Public Perception

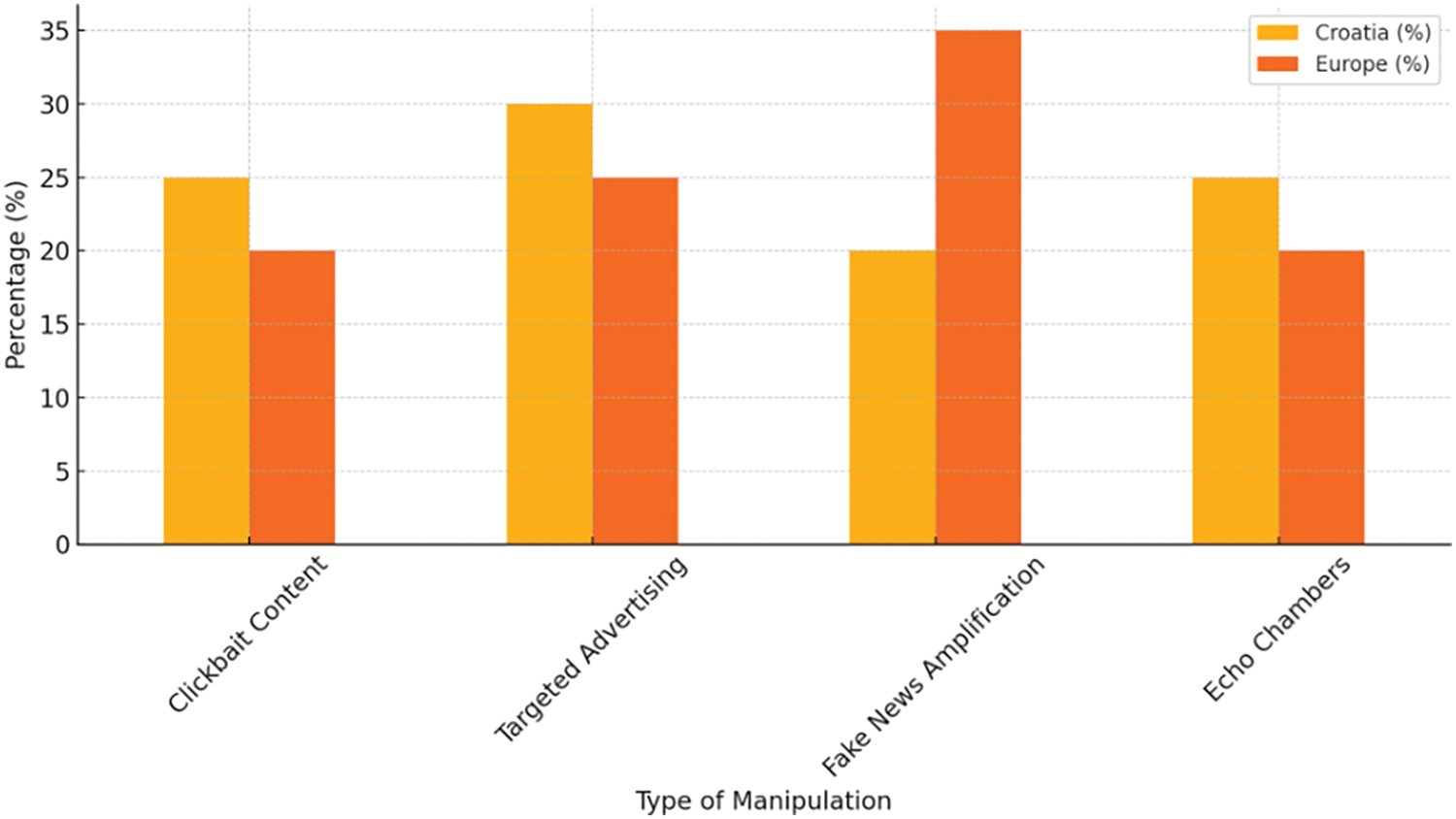

Beyond Europe, these trends are evident globally. In the United States, targeted political advertisements on platforms like Facebook and Twitter during the 2016 elections highlighted the role of algorithms in creating divisive narratives. In contrast, China’s approach integrates algorithmic manipulation with extensive state surveillance to shape public opinion and maintain strict control over information dissemination, as seen in its handling of the Hong Kong protests. These methods exploited algorithms to polarize audiences, creating ‘echo chambers’ reinforcing specific narratives. This phenomenon aligns with broader global trends where state and non-state actors utilize digital platforms to disseminate narratives and disrupt democratic processes, as evidenced by coordinated disinformation campaigns during the Syrian conflict and the U.S.-China trade war. Table II outlines the frequency of these manipulation types in Croatia and Europe. The comparative findings illustrate the distinct emphasis on national narratives in Croatia vs. pan-European discourse across broader EU contexts, reinforcing Hallin and Mancini’s theoretical assertions on media system dependence (2004).

| Type of manipulation | Croatia (%) | Europe (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Clickbait content | 25 | 20 |

| Targeted advertising | 30 | 25 |

| Fake news amplification | 20 | 35 |

| Echo chambers | 25 | 20 |

Fig. 1 visually represents this data, emphasizing the heightened role of fake news amplification in European contexts.

Fig. 1. Prevalence of algorithmic manipulation types in Croatia and Europe.

These findings align with studies highlighting the role of algorithmic amplification in exacerbating disinformation during crises (Bakshyet al., 2015; Pariser, 2011).

Comparative Analysis of Croatia and Europe

The comparative analysis of media practices in Croatia and Europe revealed substantial differences in media strategies. Croatian media systems were found to emphasize narratives aligned with national interests, while European systems promoted a more pan-European discourse. Table III summarizes these differences.

| Criterion | Croatia (%) | Europe (%) |

|---|---|---|

| National narratives | 70 | 30 |

| Pan-European discourse | 20 | 60 |

| Neutral reporting | 10 | 10 |

This distinction underscores the influence of regional sociopolitical factors on media content (Dimitrova & Stromback, 2005; Hallin & Mancini, 2004).

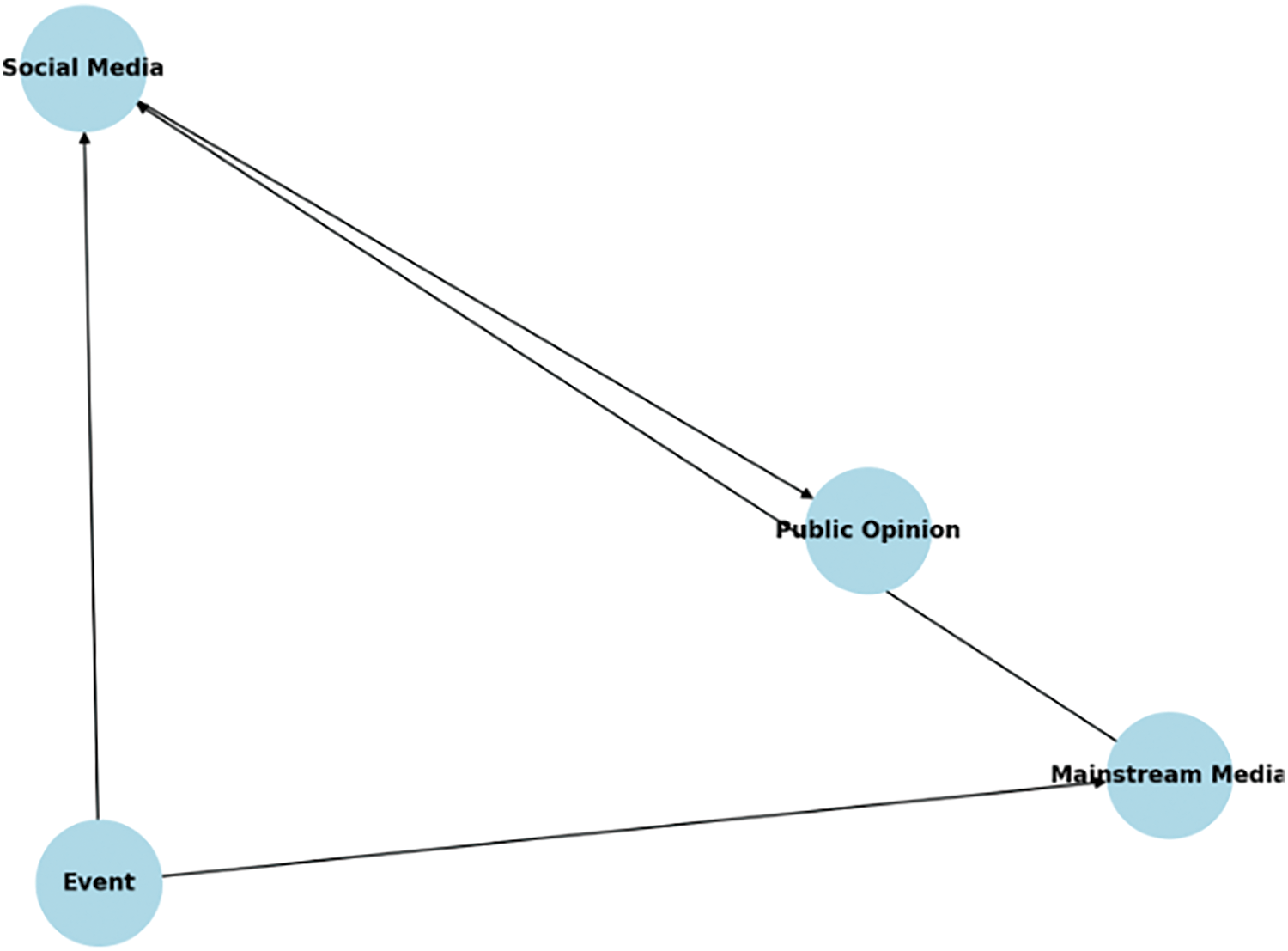

Information Flow in Media Networks

A network analysis was conducted to visualize the flow of information through media ecosystems during military conflicts. Using Gephi software, the analysis revealed the interplay between social media, mainstream media, and public opinion. Fig. 2 illustrates the pathways of information flow in media networks.

Fig. 2. Information flow in media networks during military conflicts.

This visualization highlights how social media often acts as the initial point of dissemination, influencing public opinion before being reinforced by mainstream media narratives. This finding aligns with Castells’ (2011) analysis of the network society and its implications for media systems. The visualization of information flows generated through Gephi highlights the central role of social media in amplifying polarizing narratives and influencing public opinion, thereby substantiating theoretical claims on networked information warfare by Castells (2011).

Subjective Experiences of Actors

Phenomenological analysis of interviews with journalists and military experts revealed high levels of concern regarding the biases introduced by algorithmically curated content. Approximately 85% of participants cited the proliferation of fake news as a significant threat to public understanding of military conflicts (Giles, 2016; Pomerantsev, 2014). This section concludes by emphasizing the transformative role of algorithms in military communication and their potential for both constructive and manipulative use in shaping public narratives. These findings provide a robust foundation for understanding the intersection of media theories and modern information warfare.

Discussion

Theoretical Integration

The results of this study provide critical insights into how evolving media theories intersect with military communication strategies, particularly within the contexts of Croatia and Europe. By analyzing the interplay of traditional propaganda techniques, algorithmic manipulation, and emergent frameworks like information dominance and cognitive warfare, this research contributes to a deeper understanding of modern information ecosystems. The findings demonstrate a clear application and evolution of key media theories across distinct historical and geopolitical contexts. For instance, the dominance of propaganda theory during the Croatian Homeland War aligns with Ellul’s (2021) conceptualization of propaganda as a strategic tool for mobilizing public sentiment. Similarly, algorithmic manipulation observed during the Crimea annexation resonates with Bakshyet al.’s (2015). exploration of digital echo chambers and the amplification of polarizing content through social media algorithms.

In Croatia, the reliance on nationalistic narratives, as evidenced by the results in Table II, underscores the role of framing theory in constructing socio-political cohesion during periods of conflict (Entman, 1993). On the other hand, the pan-European discourse, particularly in the NATO Kosovo intervention, highlights the nuanced application of media theories that address broader transnational narratives, as Hallin and Mancini (2004) described.

Practical Implications

These findings hold significant implications for both policymakers and military strategists. The evident rise in algorithmic manipulation, as outlined in Table I and Fig. 1, signals an urgent need for regulatory mechanisms to mitigate the spread of misinformation. Policymakers in Croatia and Europe must prioritize developing digital literacy initiatives and algorithmic transparency to counteract the harmful effects of echo chambers and fake news amplification. Furthermore, the findings underline the necessity for strategic communication frameworks that integrate both traditional media strategies and contemporary digital tools to enhance the resilience of information systems.

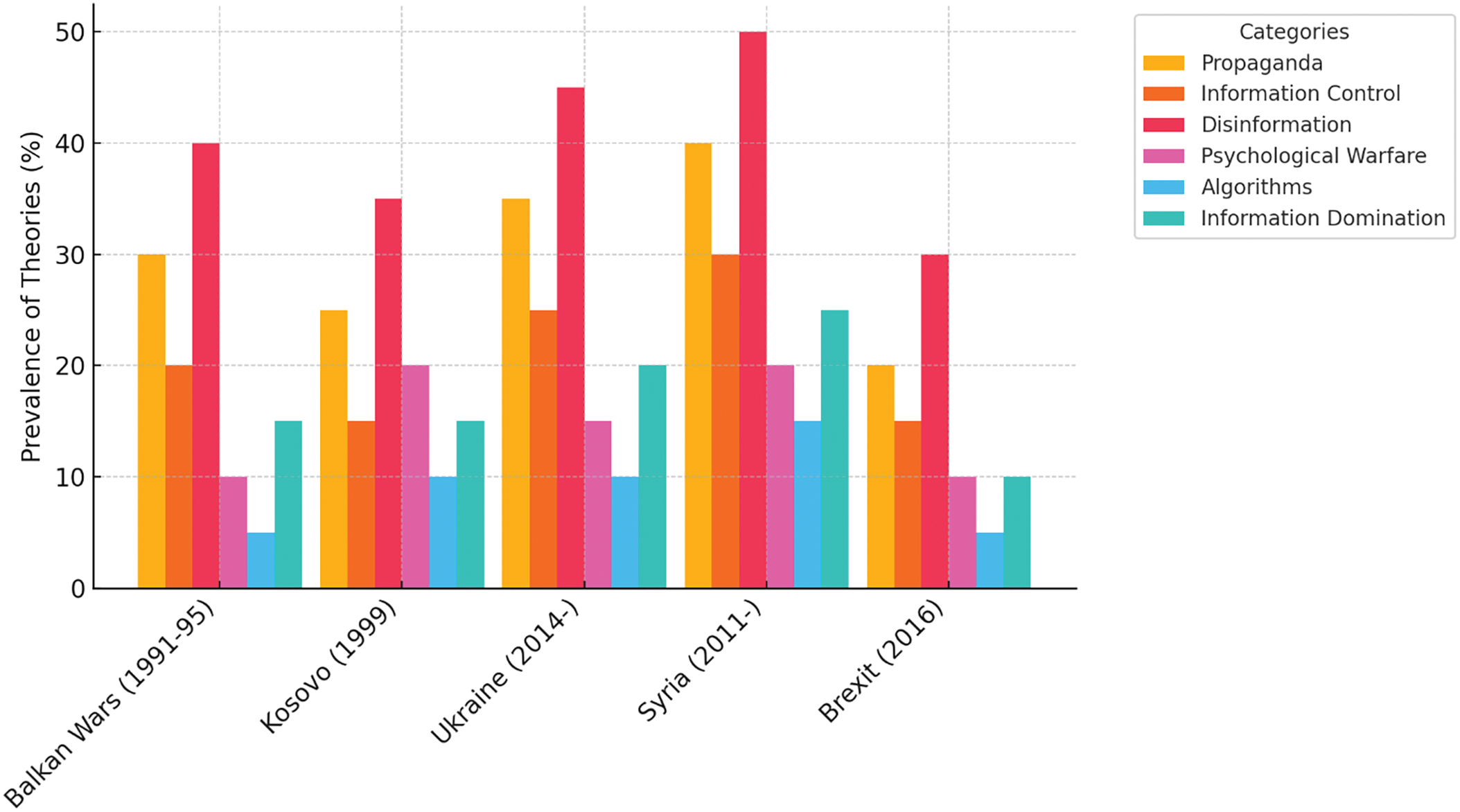

For military operations, the increasing prevalence of cognitive warfare, as revealed in qualitative interviews, emphasizes the strategic value of psychological operations and narrative control. Leveraging insights from advanced methodological tools like Gephi, as applied in network visualization (Fig. 3), can enhance the military’s ability to monitor and influence information flows in real time.

Fig. 3. Prevalence of media theories across key events over the past 30 years.

The findings of this study provide a critical lens through which the interplay between traditional and modern media theories can be examined in the context of military communications. This discussion emphasizes the strategic role of media manipulation, algorithmic frameworks, and information dominance within the evolving digital landscape by integrating theoretical, empirical, and practical dimensions. Linebarger’s early work underscores the foundational role of symbolic communication in achieving strategic military objectives (Linebarger, 1958). Smith’s examination of modern warfare strategies provides additional insight into how media manipulation integrates with military tactics to achieve strategic goals (Smith, 2012).

Theoretical Contextualization of Results

The findings in Croatia and Europe align with global trends where propaganda and information control remain pivotal. For example, in China, state-driven media heavily rely on framing theory to project narratives of national unity while suppressing dissenting views. Meanwhile, in the United States, the interplay of propaganda and algorithmic manipulation during electoral campaigns illustrates the broader application of these theories in shaping both domestic and international narratives. However, the transition to digital information ecosystems reveals a paradigm shift. Modern conflicts, such as the annexation of Crimea, highlight the increasing role of algorithmic manipulation and “echo chambers,” phenomena well-documented by Pariser (2011) and Bakshyet al. (2015). These findings demonstrate that while traditional propaganda persists, it is being increasingly augmented by sophisticated algorithmic systems designed to amplify polarizing narratives.

As depicted in Fig. 3, the relative dominance of propaganda during the Homeland War in Croatia evolved into a more hybridized strategy incorporating algorithmic tools during the Crimea conflict. This evolution reflects the integration of advanced digital technologies in military and political strategies. Similarly, as highlighted in NATO’s Kosovo intervention, information control provided a precedent for later conflicts where state actors utilized both traditional censorship and modern computational propaganda.

Practical Implications for Algorithmic Regulation and Information Control

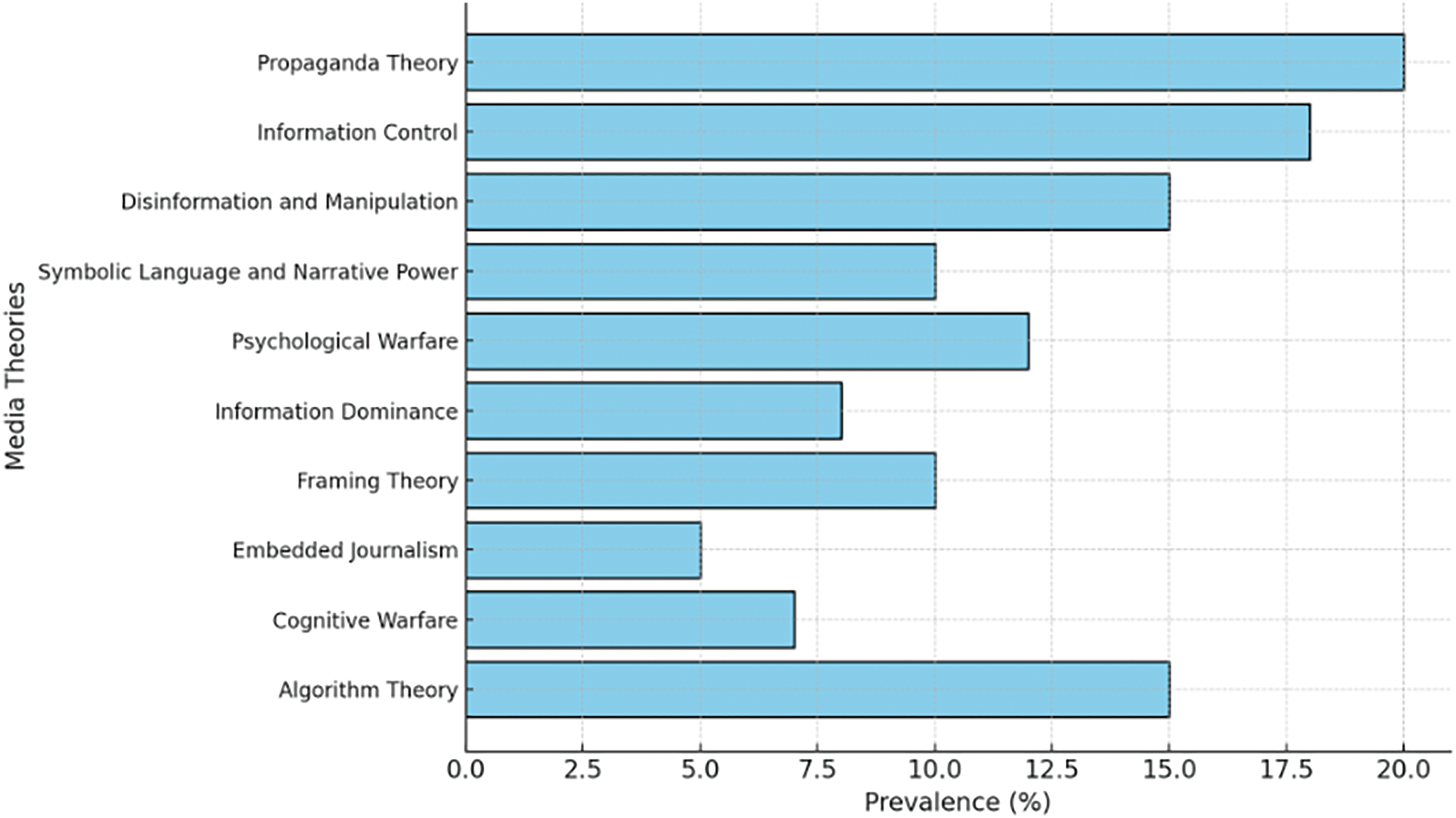

The findings reveal a pressing need for regulatory interventions to ensure greater transparency in algorithmic operations. Fig. 4 highlights the disproportionate influence of algorithmic manipulation on public opinion, particularly in digital crises such as Brexit. During this period, social media platforms leveraged targeted algorithms to propagate polarizing content, echoing the findings of Howard and Kollanyi (2016). This underscores the urgency for policymakers to establish frameworks that mitigate the risks of algorithmic manipulation, particularly in environments marked by socio-political instability.

Fig. 4. Current prevalence of media theories in European military communications.

The analysis presented in Fig. 4 highlights the prevalence of various media theories in European military communications, underscoring their significance in shaping public perception, strategic narratives, and policy directions. The data reveal that propaganda theory remains the most prominent framework, accounting for 20% of the observed cases. Propaganda has been widely used to influence public sentiment, mobilize support for military operations, and delegitimize adversaries.

For example, during NATO operations in Kosovo, propaganda campaigns were employed to generate public backing for interventions while minimizing dissent. Information control follows closely, accounting for approximately 18% of applications in military contexts. This theory emphasizes deliberately restricting or managing information dissemination to align public narratives with strategic objectives. Information control is particularly evident in conflicts such as the Ukraine crisis, where controlling the narrative was pivotal to maintaining domestic and international support.

Theories of disinformation and manipulation rank third, reflecting their growing importance in the digital age. Representing 15% of the observed cases, these theories address the strategic use of false or misleading information to disrupt enemy operations, destabilize societies, or influence public opinion. Russia’s employment of disinformation campaigns during the annexation of Crimea serves as a stark illustration of these tactics. Algorithm theory, also accounting for 15%, plays a vital role in modern military communication strategies. Algorithms shape information visibility, creating “echo chambers” that amplify specific narratives while suppressing alternative perspectives. This mechanism has been leveraged to target specific demographic groups with tailored messaging, as seen during the Brexit referendum and other politically charged events. Psychological warfare (12%) and symbolic language and narrative power (10%) remain integral to the communication strategies employed in military contexts. Psychological warfare aims to weaken adversaries’ morale through fear-inducing campaigns, while symbolic language reinforces national unity and mobilizes public sentiment in favor of military objectives.

The remaining theories, including information dominance (8%), framing theory (10%), cognitive warfare (7%), and embedded journalism (5%), reflect nuanced but critical approaches in shaping military communication. Information dominance focuses on achieving strategic control over informational environments while framing theory structures public interpretation of military events. Cognitive warfare emphasizes the manipulation of perception and decision-making processes, and embedded journalism examines the ethical implications and influence of journalists operating under military oversight. Embedded journalism, especially during military operations, raises questions about objectivity and framing. Research has shown that embedding journalists can influence the tone and content of reporting, as seen in studies from the Iraq War (Pfauet al., 2005).

The synergy between algorithmic manipulation and disinformation represents a critical threat to democratic processes. For instance, algorithm-driven amplification of disinformation campaigns significantly shaped international narratives during the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. This aligns with Giles’s conceptual framework of digital propaganda (2016), where state actors deploy computational tools to gain strategic advantages in hybrid warfare.

Fig. 3 illustrates the prevalence of key media theories—propaganda, information control, disinformation, psychological warfare, algorithms, and information dominance—across major military and political events in the last 30 years. The analysis spans conflicts such as the Balkan Wars (1991–1995), NATO intervention in Kosovo (1999), the annexation of Crimea (2014–present), the Syrian conflict (2011–present), and the Brexit referendum (2016).

During the Balkan Wars, propaganda played a pivotal role in shaping nationalistic narratives in Croatia, Serbia, and Bosnia. Croatian media, for example, heavily emphasized the ‘defense of the homeland’ and the heroism of Croatian soldiers, while Serbian media portrayed the conflict as a defense of Serbian national identity (Thompson, 1999). This propaganda dominance is reflected in its significant representation during this period in Fig. 3. Similarly, during the annexation of Crimea, the data in Fig. 3 demonstrates a shift toward algorithmic manipulation and psychological warfare, reflecting the advanced digital propaganda techniques employed by Russian state actors. Russian media platforms, including RT and Sputnik, used computational algorithms to disseminate disinformation and manipulate international narratives, a phenomenon previously documented by Pomerantsev (2014) and Nimmo (2015). In the NATO intervention in Kosovo, information control emerges as a key strategy, particularly through the censorship of unfavorable narratives by Serbian authorities. This was instrumental in maintaining public support and obscuring military failures, as Kumar (2006) described. The convergence of propaganda and information control strategies during this period is prominently depicted in Fig. 3. Algorithms and disinformation campaigns gained prominence in more recent events, such as the Syrian conflict and the Brexit referendum. The Brexit referendum serves as a case study of algorithm-driven polarization, where targeted political ads and ‘echo chambers’ amplified disinformation, significantly influencing voter perceptions (Howard & Kollanyi, 2016). This is reflected in Fig. 3 through the heightened representation of algorithms and disinformation during this period.

The trends depicted in Fig. 3 underscore the evolution of media theories in military and political contexts. Traditional approaches, such as propaganda and information control, remain relevant but are increasingly supplemented by modern algorithms and psychological warfare strategies. These findings align with Galeotti’s (2014) framework on hybrid warfare, highlighting the blending of traditional and digital strategies in modern conflicts.

Application of Advanced Methodological Tools

A notable methodological contribution of this research is the application of tools such as Gephi and MAXQDA for analyzing information networks and qualitative dana (Claverieet al., 2022; Galeotti, 2014). These tools enabled the visualization of structural patterns in information dissemination, revealing key nodes and pathways of manipulation. For example, network analysis demonstrated how targeted narratives during the Crimea conflict flowed from state-sponsored platforms to international social media, amplifying their reach and impact.

This innovative approach confirms Galeotti’s (2014) previous assertions regarding the non-linear nature of Russian information warfare. This study advances the field’s capacity to interrogate complex, multi-layered information networks by combining traditional and digital methodologies.

Future Directions: The Evolution of Information Warfare

The convergence of artificial intelligence and cognitive manipulation will likely define the future of information warfare. As Claverieet al. (2022) argued, emerging technologies will increasingly target the mental processes of decision-making, moving beyond the dissemination of information to directly influencing behavioral outcomes. This aligns with the findings of this study, which reveal a growing reliance on cognitive warfare techniques in modern military communication strategies.

In Croatia and Europe, the rise of authoritarian practices and the weaponization of digital platforms suggest a continued expansion of propaganda and algorithmic manipulation. To develop effective countermeasures, further interdisciplinary research into the intersection of sociology, political science, and information technology is necessary.

Broader Academic and Practical Implications

The results of this research make significant theoretical and practical contributions to the study of media theories in military contexts. Theoretically, this study bridges the gap between traditional frameworks and modern digital phenomena, emphasizing the adaptive nature of media strategies in response to technological advancements. Practically, it offers actionable insights for policymakers and media regulators aiming to mitigate the adverse effects of algorithmic manipulation and ensure the integrity of public discourse.

Figs. 3 and 4 illustrate that the interplay of propaganda, algorithmic manipulation, and information dominance reshape security paradigms in the digital age. The implications extend beyond the military domain, influencing democratic institutions and public trust globally.

Implications for Information Science

This research contributes significantly to the field of information science by providing insights into the organization, communication, and management of information resources in complex and dynamic environments. The application of media theories, alongside advanced methodological tools such as Gephi for network analysis and MAXQDA for qualitative data processing, illustrates the potential of interdisciplinary approaches to enhance our understanding of information systems. These contributions are not confined to military contexts but extend to broader domains such as politics, economics, and education.

In the realm of politics, the methodologies demonstrated in this study can support the analysis of political discourse, identifying patterns of misinformation and their impact on voter behavior. For instance, network visualization tools can map the flow of polarizing content across social media, providing policymakers with actionable data to counteract disinformation campaigns. Similarly, in economics, these methodologies can be leveraged to optimize the communication strategies of multinational organizations, ensuring that information reaches stakeholders in a timely and coherent manner. Moreover, the findings underline the critical role of information science in combating the proliferation of disinformation and enhancing the resilience of information ecosystems. By integrating theoretical frameworks such as cognitive warfare and algorithmic manipulation with practical tools, this research highlights how information systems can be designed to mitigate the adverse effects of echo chambers and amplify diverse perspectives. This has profound implications for building more transparent and inclusive communication environments, fostering public trust, and supporting democratic governance.

The study also underscores the importance of real-time information management in crisis scenarios. For example, the tools and approaches applied here can be adapted for disaster response or public health crises, where timely dissemination of accurate information is crucial. Advanced systems powered by artificial intelligence could play a pivotal role in these contexts, enabling dynamic analysis of information flows and rapid adjustment of communication strategies to meet evolving needs.

In conclusion, integrating media theories and advanced analytical tools offers a robust framework for addressing contemporary challenges in information science. By bridging theoretical insights with practical applications, this research provides a foundation for developing innovative approaches to information organization, communication, and management, ultimately contributing to creating more robust and adaptive information systems across diverse domains.

The methodological innovations presented in this study, such as integrating network visualization with qualitative content analysis, pave the way for new applications in real-time crisis communication and disaster response. By extending the scope of media theories into dynamic information systems, this research contributes to building resilient frameworks capable of addressing the challenges of the digital age in domains as diverse as cybersecurity, governance, and global public health.

Conclusion

This study has explored the interplay between media theories and military communication strategies in Croatia and Europe, contextualizing their evolution over the last 30 years. The research has provided a nuanced understanding of how traditional and modern media theories shape public perception and strategic narratives by analyzing the application of propaganda, framing, and information control alongside algorithmic manipulation and cognitive warfare. The findings emphasize the enduring relevance of classical theories such as propaganda and framing, which remain pivotal in conflict-driven narratives. During the Croatian Homeland War, media relied heavily on propaganda to galvanize public sentiment and foster national unity. This strategic use of media illustrates how framing theory constructs socio-political cohesion during periods of heightened national vulnerability. Similarly, propaganda and information control have been integral in transnational conflicts in Europe, such as NATO’s Kosovo intervention, where these approaches shaped both domestic and international narratives. The study also highlights the transformative impact of digital technologies, particularly algorithmic manipulation and disinformation, on military communication. Events like the annexation of Crimea and the Brexit referendum illustrate how algorithms and digital platforms amplify polarizing content, creating echo chambers that shape public opinion. These developments underscore the need to reframe media theories to account for the computational tools and data-driven strategies that now dominate the information landscape. Propaganda remains a pivotal tool in shaping public sentiment during conflicts, with historical accounts and modern applications underscoring its significance (Ingram, 2016; Jowett & O’Donnell, 2018; Taylor, 2013).

A key insight of this research is the shift from traditional media strategies toward hybrid approaches that combine propaganda and information control with advanced digital tactics. This evolution reflects the growing role of algorithm-driven narratives and cognitive warfare in contemporary conflicts. As demonstrated in the findings, algorithmic manipulation has emerged as a critical tool in modern hybrid warfare, challenging the integrity of public discourse and democratic processes. This calls for robust regulatory frameworks to ensure transparency in algorithmic operations and mitigate the risks of disinformation campaigns.

Croatia’s continued reliance on nationalistic narratives reflects the historical and cultural specificity of its media ecosystem, which contrasts with broader European trends. While Croatia’s media strategies focus on nation-building and post-conflict reconstruction, European approaches often integrate broader transnational and algorithm-driven narratives to address geopolitical challenges. This divergence highlights the importance of understanding localized media practices within the broader context of global information warfare.

The study also underscores the critical role of advanced methodological tools, such as network analysis and qualitative data software, in analyzing modern information systems. These tools revealed key patterns in the dissemination of information, particularly during the Crimea conflict, where targeted narratives flowed from state-sponsored platforms to international digital ecosystems. Applying such methodologies enhances the understanding of information warfare and provides actionable insights for policymakers and military strategists. The integration of artificial intelligence and cognitive manipulation into military communication strategies will likely define the next phase of information warfare. Looking forward, the integration of AI into information systems presents both opportunities and challenges for communication strategies. ‘Smart information systems,’ powered by AI and real-time analytics, have the potential to enhance efficiency and precision in managing information flows, especially in complex environments. However, their dual-use nature also raises ethical concerns, particularly regarding the manipulation of public opinion and the amplification of disinformation. Policymakers and technologists must collaborate to ensure these tools are employed responsibly, balancing their potential for innovation with the need to uphold democratic values.

Emerging technologies will enable increasingly precise targeting of public opinion, shifting the focus from controlling information flows to directly influencing decision-making processes. This underscores the importance of interdisciplinary research to address these developments’ ethical, political, and technological challenges. This research bridges traditional media theories with modern digital phenomena, contributing to a deeper understanding of how media shape military and political communication in the digital age. By integrating theoretical, empirical, and practical dimensions, the study provides a foundation for further exploring information warfare and its implications for democratic institutions and global security. This convergence is not limited to Croatia and Europe. Globally, countries like the United States and China exemplify how these phenomena manifest differently across democratic and authoritarian systems, reflecting the universal relevance of media theories in addressing the complexities of information warfare. Future research should further explore these dynamics to develop globally applicable strategies for mitigating disinformation and reinforcing democratic resilience.

The interdisciplinary nature of this research, combining media theories, computational tools, and geopolitical analysis, underscores the importance of collaboration across fields in addressing complex challenges posed by information warfare. By integrating insights from sociology, political science, and computer science, this study sets a precedent for future research aiming to navigate the intricacies of digital ecosystems in a globalized world.

References

-

Bacevich, A. J. (2005). The new American militarism: How Americans are seduced by war. Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

1

-

Bakshy, E., Messing, S., & Adamic, L. A. (2015). Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook. Science, 348(6239), 1130–1132. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa1160

Google Scholar

2

-

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Google Scholar

3

-

Castells, M. (2011). The rise of the network society. John Wiley & Sons.

Google Scholar

4

-

Chomsky, N., & Herman, E. S. (1989). Political economy of the mass media. David Barsamian/Alternative Radio.

Google Scholar

5

-

Claverie, B., Prébot, B., Buchler, N., & Du Cluzel, F. (2022). Cognitive warfare: The future of cognitive dominance. Bruxelles: NATO Science and Technology Organization.

Google Scholar

6

-

Dimitrova, D. V., & Stromback, J. (2005). Mission accomplished? Framing of the Iraq War in the elite newspapers in Sweden and the United States. International Journal of Press/Politics, 10(4), 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161205278123

Google Scholar

7

-

Ellul, J. (2021). Propaganda: The formation of men's attitudes. Vintage.

Google Scholar

8

-

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

Google Scholar

9

-

Galeotti, M. (2014). The Gerasimov doctrine and Russian non-linear war. Moscow’s Shadows, 6(7).

Google Scholar

10

-

Gerbner, G., & Gross, L. (2017). Living with television: The violence profile. In The fear of crime (pp. 169–195). Routledge.

Google Scholar

11

-

Giles, K. (2016). Russia’s “new” tools for confronting the West: Continuity and innovation in Moscow’s exercise of power. London: Chatham House.

Google Scholar

12

-

Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the internet: Platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media. Yale University Press.

Google Scholar

13

-

Habermas, J., & Press, P. (1989). The public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society.

Google Scholar

14

-

Hallin, D. C., & Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing media systems: Three models of media and politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Google Scholar

15

-

Herman, E. S., & Chomsky, N. (1988). Manufacturing consent: The political economy of the mass media. Pantheon Books.

Google Scholar

16

-

Herman, E. S., & Chomsky, N. (2002). Manufacturing consent: The political economy of the mass media. Pantheon Books.

Google Scholar

17

-

Howard, P. N., & Kollanyi, B. (2016). Bots, #strongerin, and #brexit: Computational propaganda during the UK-EU referendum. arXiv preprint. https://arxiv.org/abs/1606.06356

Google Scholar

18

-

Ingram, H. J. (2016). Deciphering the siren call of militant Islamist propaganda: Meaning, credibility and behavioural change. The Hague: The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism.

Google Scholar

19

-

Jakubowicz, K., & Sukosd, M. (2008). Finding the right place on the map: Central and Eastern European media change in a global perspective. Intellect Books.

Google Scholar

20

-

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. New York: New York University Press.

Google Scholar

21

-

Jowett, G. S., & O'Donnell, V. (2018). Propaganda & persuasion. Sage Publications.

Google Scholar

22

-

Katz, E., Lazarsfeld, P. F., & Roper, E. (2017). Personal influence: The part played by people in the flow of mass communications. Routledge.

Google Scholar

23

-

Kumar, D. (2006). Media, war, and propaganda: Strategies of information management during the 1999 Kosovo War. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, 3(1), 48–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/14791420500505650

Google Scholar

24

-

Linebarger, P. M. (1958). Leadership in the Western Pacific and Southeast Asia. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 318(1), 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271625831800107

Google Scholar

25

-

Londo, I., Jusić, T., Popova, V., Malović, S., Šmíd, M., Paju, T. & Trpevska, S. (2004). Media ownership and its impact on media independence and pluralism. Peace Institute, Institute for Contemporary Social and Political Studies.

Google Scholar

26

-

McCombs, M. E., & Shaw, D. L. (1972). The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly, 36(2), 176–187. https://doi.org/10.1086/267990

Google Scholar

27

-

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Schulz, A., Andi, S., Robertson, C. T., & Nielsen, R. K. (2021). Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2021. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2021

Google Scholar

28

-

Nimmo, B. (2015). Anatomy of an info-war: How Russia’s propaganda machine works, and how to counter it. Central European Policy Institute, 15, 1–16.

Google Scholar

29

-

Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: What the internet is hiding from you. New York: Penguin Press.

Google Scholar

30

-

Pfau, M., Haigh, M. M., Logsdon, L., Perrine, C., Baldwin, J. P., Breitenfeldt, R. E., Cesar, J., Dearden, D., Kuntz, G., Montalvo, E., Roberts, D., & Romero, R. (2005). Embedded reporting during the invasion and occupation of Iraq: How the embedding of journalists affects television news reports. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 49(4), 468–487. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15506878jobem4904_5

Google Scholar

31

-

Pomerantsev, P. (2014). Nothing is true and everything is possible: The surreal heart of the new Russia. Public Affairs.

Google Scholar

32

-

Shin, J., & Thorson, K. (2017). Partisan selective sharing: The biased diffusion of fact-checking messages on social media. Journal of Communication, 67(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12284

Google Scholar

33

-

Smith, R. (2012). The utility of force: The art of war in the modern world. London: Penguin.

Google Scholar

34

-

Splichal, S. (2001). Public opinion: Developments and controversies in the twentieth century. Rowman & Littlefield.

Google Scholar

35

-

Sundar, S. S., & Limperos, A. M. (2013). Uses and grats 2.0: New gratifications for new media. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 57(4), 504–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2013.845827

Google Scholar

36

-

Taylor, P. M. (2013). Munitions of the mind: A history of propaganda from the ancient world to the present era. Manchester University Press.

Google Scholar

37

-

Thompson, M. (1999). Forging war: The media in Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia, and Hercegovina. University of Luton Press.

Google Scholar

38

-

Weaver, D. H. (2007). Thoughts on agenda setting, framing, and priming. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 142–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00333.x

Google Scholar

39

Most read articles by the same author(s)

-

Marija Gombar,

Modernizing Military Outreach: Social Media and the Future of Youth Engagement in Croatia , European Journal of Communication and Media Studies: Vol. 4 No. 2 (2025) -

Marija Gombar,

Enhancing Public Support Through Modern Communication Strategies: A Study on Croatian Military Relations and Recruitment Dynamics , European Journal of Communication and Media Studies: Vol. 4 No. 1 (2025)