Is there a Gender Bias in Media Representations of Consumer Food Sustainability?

Article Main Content

This study investigated the potential gender bias in media representations of consumer food sustainability through a quantitative content analysis of 287 Danish newspaper articles. Drawing on media framing and agenda-setting theories, we explored how journalists’ gender influences the framing of sustainability issues. The analysis identifies significant relationships between frame content (e.g., consumers’ responsibility and ethical considerations) and implications (e.g., sustainable consumption), with notable gender-based differences. The results suggest that female journalists are more likely to emphasize economic considerations as influencing sustainable consumer shopping, whereas male journalists tend to highlight consumers’ responsibility and motivations as key factors shaping such behavior. These findings suggest that gender plays a moderating role in the construction of sustainability narratives in media. This study highlights the importance of gender diversity in journalism to ensure balanced and inclusive coverage of societal challenges, offering implications for media practices and public policy communication strategies.

Introduction

Consumer food sustainability can be viewed as an important societal challenge, encompassing critical aspects, such as its impact on the environment and climate (Poore & Nemecek, 2018; Hansen, 2022). Food production, distribution, and consumption are related to deforestation, greenhouse gas emissions, and biodiversity loss (e.g., Crosbyet al., 2021). Additionally, sustainable food practices (e.g., reducing meat consumption and food waste) are essential to ensure that future generations have access to nutritious and affordable food (Liuet al., 2023). Hence, consumer food sustainability is a multifaceted concept encompassing environmental, economic, and social aspects (Conrad & Blackstone, 2021).

We suggest that the public’s views and opinions on matters of public interest, such as consumer food sustainability, may be shaped and reflected in the media (Geschkeet al., 2010; Hansen, 2020; Kingdon, 1995; McCombs, 2004; Naser, 2020; Goyanes & Cañedo, 2024). Media framing theory also suggests that the way an issue is framed - by emphasizing certain aspects - can influence how people interpret and respond to it (e.g., Buturoiuet al., 2023; Bellotti & Panzone, 2016). Although editors and journalists often maintain that newspaper articles are impartial and accurate, the media has frequently faced accusations of biased reporting, perpetuating stereotypes, and other criticisms (Spindeet al., 2022; Geschkeet al., 2010). While it is known that several factors might influence media framing of various topics, including existing public discourse and citizen action surrounding a given topic (Paveglioet al., 2011), source or quote selection, sponsors, reporter preferences (such as motivations, objectives, and purposes of article writers), the gender of the person in focus (e.g., the gender of a political candidate), and individuals of special interest (Van der Pas & Aaldering, 2020; Entman, 2004; Paveglioet al., 2011), less attention has been paid to the gender of journalists writing articles within a media theoretical context. This is unfortunate because the gender of a journalist may potentially influence the framing and focus of news stories, and ultimately the relationships between frame content and implications.

Research has shown that male and female journalists may approach topics differently, potentially leading to varied representations of societal issues such as consumer food sustainability. For example, male journalists might emphasize individual aspects, whereas female journalists might focus more on social and environmental impacts (Ruoho & Torkkola, 2018; North, 2016). Moreover, gender bias in journalism can perpetuate stereotypes and limit the diversity of voices and viewpoints in media. Additionally, studies have found that women are often underrepresented in news coverage, both as journalists and sources (Davidson & Greene, 2024). This underrepresentation can skew the portrayal of societal challenges, leading to a less comprehensive understanding of societal issues, such as food sustainability. Thus, addressing the potential gender bias in journalism is essential to ensure that media coverage is balanced and inclusive. By recognizing and mitigating these biases, a more equitable and accurate representation of important societal challenges can be promoted, ultimately contributing to more informed public discourse and better policy outcomes.

Based on these notions, this study performed a quantitative media content analysis of 287 newspaper articles that discussed consumer food sustainability. While most studies classify and identify consumer-related sustainability issues through surveys, experiments, or interviews, the present study’s methodology is different from previous research in that it simultaneously (a) examines consumer food sustainability from a media perspective, (b) focuses on journalists’ gender in investigating the framing of consumer food sustainability issues, and (c) explores the relationships between frame content and implications.

Theoretical Background

Media Theory and Consumer Food Sustainability

The presence of media as an information and knowledge resource is important for contemporary societies to operate and for citizens to engage with and understand topics relevant to their behavior and social lives. Mass media influences public opinion by shaping topics that capture public attention (McCombs, 2004). The transmission of salient issues from the media agenda to the public agenda and opinion relies on the assumption that the public is interested in information provided by the media. However, it is important to recognize that such information, though often aligned with public interests, is curated by journalists and editors, as McCombs (2004) points out. Media agenda-setting theory proposes that public matters may reach the media agenda through various streams such as political streams (e.g., recent political events), policy streams (e.g., introduction of new policy tools such as carbon taxes), or problem streams (e.g., natural disasters) (Hansen, 2020; Kingdon, 1995). In this regard, Geschkeet al. (2010) suggest that media coverage does not just affect attitudes based on what is reported but also by how it is presented.

According to media framing theory, media considers public views, interests, and opinions when selecting how to convey and frame a story. Therefore, media framing theory differs from media agenda-setting theory in several respects. While media agenda-setting theory focuses on the importance and prominence of topics by determining which issues are highlighted and brought to public attention, media framing theory focuses on how these issues are presented in the media (e.g., Buturoiuet al., 2023; Entman, 2004). Media agenda-setting is concerned with what the media tells the public to think about, whereas framing is about how the media shapes and reflects the public’s opinion of these issues.

By focusing on the specific elements of a topic, media framing theory provides a useful perspective on how the media may influence public opinion. While a topic can have multiple perspectives and interpretations (Bellotti & Panzone, 2016), Goffman (1974) states that frames can assist readers in “finding, observing, identifying, and naming the flow of information around them.” According to McCombs (2004) and Hansen (2020), frames are thought to represent how individuals create impressions and perspectives on a variety of topics by selecting and addressing particular aspects of those topics. In this regard, it is important to distinguish between the implications and content of the frame. While frame implications are suggested specific treatment recommendations, frame contents can be conceptualized as the selection of certain parts of seeming reality to increase their relevance (Entman, 2004). Accordingly, frame contents are essential notions or stories that establish the framework of an environment and provide a contextual setting for abstract or complex issues such as consumer food sustainability. Frame implications emphasize potential actions, making it more likely for citizens to understand the possible implications of frame content (McCombs, 2004; Hansen, 2020).

Frames should be considered in connection with a certain subject, event, or actor because they can vary greatly across different issues (Entman, 2004). Consumer food sustainability and framing have been the topic of several studies in previous research, and many interesting results have demonstrated the viability of the media framing approach. For instance, Bellotti and Panzone (2016) used a content analysis of newspaper articles on organic food. Their qualitative approach indicated that the way news is framed is important. Specifically, their findings suggest that information may be more effective in influencing product purchases when sustainable food products are presented uncritically in news. In a study of the framing of consumer food sustainability in newspaper articles, Hansen (2022) found that the Covid-19 pandemic has positively influenced consumers’ sustainability consciousness and that consumers show an increased willingness to spend more on environmentally friendly food. The results obtained by these studies highlight that frame analysis is a viable research method for understanding how news media presents various topics and issues related to consumer food sustainability.

However, even though prior studies have emphasized the significance of consumer- and food-related frames in comprehending media and public opinions and behavior, the present study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to investigate how relationships between frame implications and frames related to consumer food sustainability may appear in the media while accounting for the possible influence of journalists’ gender.

Media and Gender Theory

Gender socialization theory suggests that a person’s thoughts, feelings, and behavior are largely influenced by the cultural values, beliefs, and practices that they encounter in society (Nobleet al., 2006; Thompsonet al., 2022). Accordingly, gender disparities may cause men and women to use different socially built cognitive frameworks to encode information and develop motives, which may then be related to their behavior (Smith & Floro, 2020; Venkatesh & Morris, 2000). In that respect, empirical evidence suggests that women might be more likely to think about the wider effects of their actions, whereas males are more likely to prioritize performance and financial gain. For example, women might place more importance on things like leading a healthy lifestyle, whereas males tend to emphasize financial achievement (Kouchaki & Kray, 2018).

As societies become more aware of the environmental and ethical consequences of food consumption, journalists play an increasingly important role in influencing public discourse and opinions on food and sustainability. In this regard, journalists may bring their personal experiences and perspectives into play to a certain extent. Social role theory (e.g., Stanzianiet al., 2024; Steiner, 2012; Komarovsky, 1992) implies that journalists’ gender can be an important factor that may contribute to shaping the framing of consumer food sustainability. This is because societal roles and expectations may affect how journalists approach important societal challenges. Traditional roles related to food and care may lead female journalists to experience a stronger connection with sustainability issues, which may ultimately affect their coverage. Conversely, male journalists may feel tempted to focus on issues related to business and technology. Specifically, female journalists could conceivably emphasize the impact on the well-being of the family and society, as well as the ethical considerations of food production. Male journalists are likely to focus on technological advances and the political aspects of food and sustainability.

Journalists can also seek to adapt content to their perceived audience. For example, if a journalist has the experience that the readership in question has gender-based interests, this might influence the chosen approach to the subject. Thus, female journalists may be inclined to write articles that are more targeted at a female audience, including highlighting practical tips for a sustainable lifestyle and the social consequences of sustainable food behavior. By contrast, male journalists may be more likely to target their articles to an audience interested in slightly broader environmental consequences (Ruoho & Torkkola, 2018). Additionally, the choice of sources and background content may vary between female and male journalists. Female journalists may have a greater tendency to prioritize sources and studies exploring the social and health consequences of sustainable food practices, whereas male journalists may focus more on research and content related to, for example, trends and technological innovations in the food industry (e.g., Jamilet al., 2020; Steiner, 2012). These potential differences in source selection may have led to varied presentations on the same topic.

Research Questions

This research adopts an exploratory approach to analyze the relationships between various frame contents and their implications, as detailed in the Methodology section. In total, we investigated 20 direct relationships between frame content and implications, along with 2 × 20 moderating influences (i.e., gender as a moderator). Many of these relationships are explored for the first time in this study, suggesting that formulating formal hypotheses for each direct and moderating effect may be premature. Additionally, developing hypotheses for such a vast array of relationships could result in a dense and convoluted presentation of the results. Instead, we developed broader research questions to streamline the communication of findings and make them more accessible to the readers.

Building on this notion and drawing from media framing theory, we investigate ‘how’ the message is presented, focusing on two main framing constructs: the presentation of the issue or topic (i.e., frame contents) and the presentation of suggested treatments, consequences, or necessary actions (i.e., frame implications). Specifically, investigating the relationships between specific frame contents and implications allows for an understanding of how narrative structures may influence the construction of public opinion. Thus, our first research question was as follows:

RQ1: What are the relationships between frame content and frame implications in the media representations of consumer food sustainability?

While RQ1 focuses on the direct relationships between frame content and implications, it also represents an important first step toward understanding the consequences of including gender considerations in the analysis (i.e., RQ2 below). By examining how specific frame content relates to the implications promoted in media narratives, RQ1 serves as a foundation for identifying the framing consequences that emerge when gender is introduced as a relationship moderator.

As argued above, we specifically address journalists’ gender as a potential moderator of the relationship between frame content and implications. Thus, we propose the second research question:

RQ2: To what extent does journalists’ gender moderate the relationships between frame contents and frame implications in media representations of consumer food sustainability?

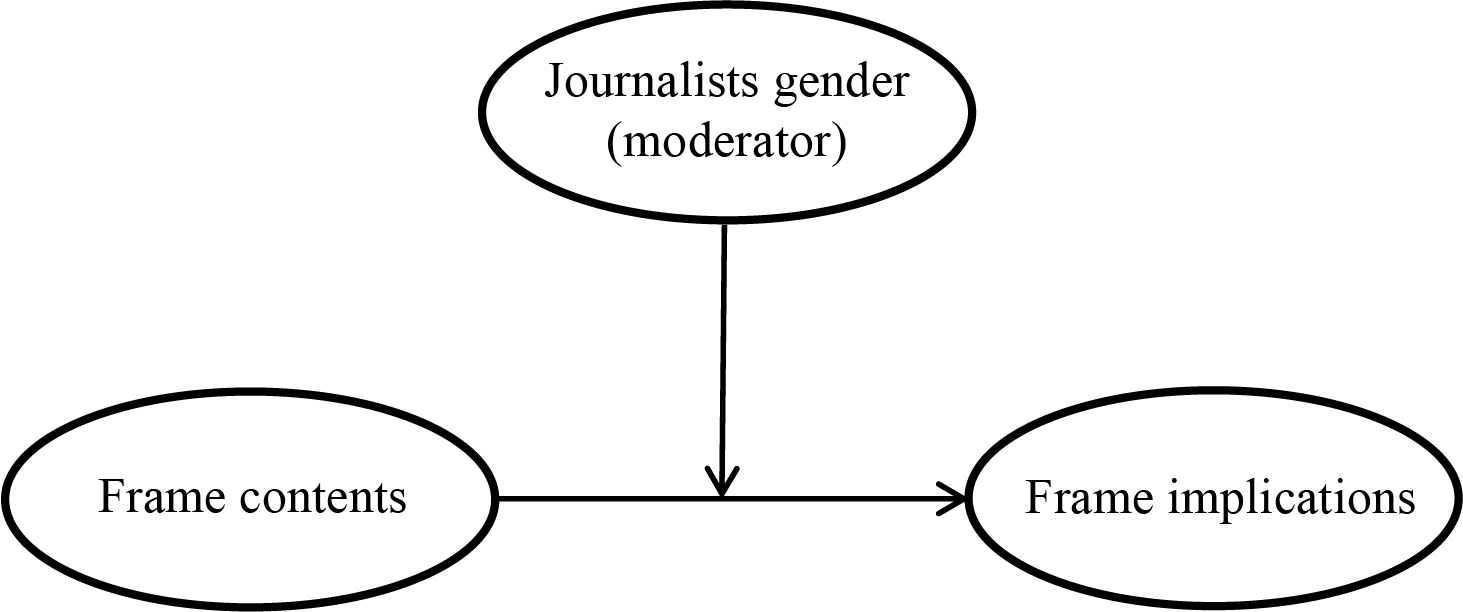

Fig. 1 summarizes the study’s purpose, including the investigation of direct relationships between frame contents and implications (RQ1), as well as the moderating role of journalist gender in shaping these relationships (RQ2).

Fig. 1. Conceptual framework: Gender bias in media framing of consumer food sustainability.

Methodology

We utilized a deductive procedure to identify the relevant frame content and implications for this study (Hansen, 2020; Dirikx & Gelders, 2010; Semetko & Valkenburg, 2000). A thorough examination of scholarly literature and mainstream media perspectives on consumer food sustainability revealed a variety of frame content and implications. First, an extensive review of the popular press and research literature on consumer food sustainability conducted by Hansen (2022) suggests several highly relevant frame contents and implications for investigating food sustainability issues. Second, an additional review of recent research (e.g., Sonck-Rautioet al., 2025; Béné & Abdulai, 2024; Mouchtaropoulouet al., 2024; HealthFocus International, 2020; Nichiforet al., 2025; Mešićet al., 2024; Reppmannet al., 2024; Principatoet al., 2021) related to consumer food sustainability strongly indicated the appropriateness of these frame contents and implications for the present study.

To investigate the presence of frame contents and implications in newspaper stories, a set of 30 questions (items) was then developed using the procedures suggested by previous research (e.g., Hansen, 2020; Klineet al., 2006): First, each construct was carefully defined based on past research (see Appendix A for literature examples). For example, a ‘consumer motivations’ frame could be defined as media content that ‘highlights how consumer food sustainability relates to consumer motivations and expectations. ‘ Second, based on the literature, the initial items were developed to represent each construct. These items are specific statements or questions that can be used to assess the presence of a construct in media content. For example, an item for a ‘sustainable production methods,’ frame could be ‘does the article indicate that raw materials should be sourced sustainably?’ Each question aimed to measure one of the five frame contents: consumers’ responsibility, others’ responsibility, economic considerations, ethical considerations, and consumer motivations, or one of the four frame implications: sustainable production methods, sustainable selling methods, sustainable consumer shopping, and sustainable consumption.

To assess the applicability of the frame measures, a pilot study was conducted on 50 randomly chosen articles identified through the Infomedia database, a comprehensive news media database that includes almost all Danish nationwide, regional, and local newspapers, along with other news and media sources such as magazines and popular journals. The search, which included national outlets as well as regional newspapers and magazines, was conducted in December 2024 (article search period: January 1, 2024, to November 30, 2024), utilizing the key search terms ‘food’, ‘consumer(s)’, and ‘sustainability/sustainable’.

The frame contents/implications of the 50 articles were discussed and adjusted based on inputs from both primary and secondary coders. Although no new frames were added, a few existing items were refined to enhance comprehension and reduce uncertainty in the subsequent coding process. Following this methodology (e.g., Eloet al., 2014), the quantitative content analysis comprised five frame contents and four frame implications, encompassing 30 items. An additional 25 articles with the same search period and outlet criteria as in pilot study 1 were then analyzed to further pilot test the frame contents and implications, resulting in no further modifications or additions to the frames or items. Appendix B provides the final frames and items.

In the main study, 350 additional newspaper stories were identified through Infomedia. The search strategy paralleled that of the pilot studies, focusing on the key search terms ‘food’, “-” ‘consumer(s)’, and ‘sustainability/sustainable’. The search was conducted in March 2025 (article search period: June 1, 2023, to February 28, 2025). A longer search period was used for the main study than for pilot studies 1 and 2 to facilitate the collection of a larger dataset. Of the 350 stories, 63 stories, primarily comprising statistical summaries of consumers’ shopping or eating patterns, were excluded from the analysis. The final sample consisted of 287 stories dated June 4, 2023, to February 25, 2025. The average length of the retrieved newspaper stories was 552 words, with the shortest story consisting of 182 words and the longest extending to 3,342 words.

In this study, journalists were classified as male or female based on their names. This binary classification is based on practical considerations and the need for a clear, operationalizable variable for statistical analysis, while acknowledging the existence of non-binary and other gender identities. In Denmark, approximately 0.5%–1.4% of the population is identified as transgender or non-binary (DIHR - Danish Institute for Human Rights, 2025), limiting this bias to a reasonably low level. Only articles written by a single, clearly named journalist were included in this study.

The 30 questions had two coders who coded the answers and assigned a yes (1) or no (0) response. To evaluate the robustness of the study’s conclusions, the secondary coder classified 104 randomly selected articles, whereas the primary coder categorized all 287 articles (Eloet al., 2014). An expert in food and sustainability research served as the primary coder, whereas a non-expert with academic knowledge of societal issues served as the secondary coder. The inter-coder reliability was 91.1%, and the reliability of two sub-samples of 40 randomly selected articles was 91.4% and 90.8%, respectively, indicating adequate reliability of the coding (e.g., Dirikx & Gelders, 2010). All the coded schemes met the alpha requirement of 0.70 (Nunnally, 1978) (see the Results section and Table I). The content analysis of the main coder forms the basis of the estimated results. These data are available at https://osf.io/dmxqw/files/osfstorage.

| Dimension | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 54/53 | |||||||||

| 1. Consumers’ Responsibility | 107 | 47/46 | |||||||

| 2. Others’ Responsibility | 0.19a | 93 | 27/23 | ||||||

| 3. Economic Considerations | −0.03 | 0.09 | 50 | 45/47 | |||||

| 4. Ethical Considerations | 0.23a | −0.02 | 0.03 | 92 | 65/65 | ||||

| 5. Consumer Motivation | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.25a | 130 | 59/48 | |||

| 6. Sustainable Production Methods | 0.01 | 0.31a | 0.12b | 0.09 | 0.04 | 107 | 14/22 | ||

| 7. Sustainable Selling Methods | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.05 | 0.13b | 0.09 | 36 | 19/11 | |

| 8. Sustainable Consumer Shopping | 0.26a | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.13b | 0.14b | 0.04 | −0.03 | 30 | 48/42 |

| 9. Sustainable Consumption | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.21a | 0.78a | 0.06 | 0.16a | 0.11 | 90 |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.72 | 0.85 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.82 |

Results

Statistical Procedures

Categorical principal component analysis (CatPCA) was used to estimate the factor scores for the frame constructs. CatPCA employs optimal scaling to handle a wide range of variables, including binary ones. CatPCA converts binary variable categories to numeric value variables without assuming linearity between variable associations (Kemalbay & Korkmazoğlu, 2014). The CatPCA procedure was carried out sequentially, with each construct being investigated individually. This method allows for a more straightforward interpretation of the factors, prevents factor mixing across constructs, and provides a more accurate representation of the underlying items. First, we examined factor loadings and eliminated items with loadings less than 0.50, a commonly used threshold in research (e.g., Semetko & Valkenburg, 2000). None of the items were excluded from this study. Next, the factor scores and construct reliabilities (i.e., Cronbach’s alpha values) were estimated. The CatPCA dimension correlation matrix (Table I) revealed numerous significant correlations between the frame content and implications. In Table I, numbers on the diagonal represent the number of times (averaged across items) a particular frame was coded 1 in the content analysis. Numbers above the diagonal represent the number of times (averaged across items) a particular frame was coded 1 in the content analysis by male journalists/female journalists, respectively.

Numbers below the diagonal represent correlations among CatPCA dimensions.

This suggests that determining path relationships between these dimensions is a feasible strategy. Nevertheless, the standard maximum likelihood (ML) estimator’s distributional assumptions may be violated by the introduction of non-normality brought about by the use of CatPCA dimensions. Therefore, we employed a bootstrapping resampling procedure (5,000 samples) to estimate the path model and produce appropriate distributional chi-square statistics and standard errors. Subsequently, we used to reestimate the models. A comparison of parameter estimates using bootstrapping and ML revealed that all estimated structural equation modeling paths had similar significance levels. The results based on the ML estimates are presented in the following section.

All frame constructs met the basic research guideline alpha requirement of 0.70 (Nunnally, 1978). Discriminant validity was assessed using CatPCA component loadings to estimate the extracted variance associated with each construct. In all incidents, the extracted variance (ranging from 0.63 to 0.89) for each individual construct was greater than the squared correlation (i.e., shared variance) between constructs (Table I), suggesting sufficient discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Results Pertaining to RQ1: Main Effects

We employed SPSS AMOS 29 and path analysis to estimate the relationships between the frame content and frame implications. An estimation of the path model showed a reasonable fit (χ² = 7.83, df = 6, p = 0.25; goodness-of-fit index [GFI] = 0.98; comparative fit index [CFI] = 0.99; normed fit index [NFI] = 0.99; root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] =0.033). Several significant relationships between frame content and frame implications were identified (Table II).

| Main effects | Moderating effects of journalists’ gender | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||

| Relationship | β(SE) | β(SE) | β(SE) |

| Consumers’ responsibility →Sustainable production methods | −0.08 (0.06) | −0.08 (0.09) | −0.08 (0.18) |

| Consumers’ responsibility →Sustainable selling methods | −0.10 (0.06) | −0.05 (0.08) | −0.14 (0.09) |

| Consumers’ responsibility →Sustainable consumer shopping | 0.24a (0.06) | 0.41a (0.10) | 0.01 (0.05) |

| Consumers’ responsibility →Sustainable consumption | −0.04 (0.02) | −0.03 (0.03) | −0.06b (0.03) |

| Others’ responsibility →Sustainable production methods | 0.32a (0.06) | 0.32a (0.08) | 0.31a (0.08) |

| Others’ responsibility →Sustainable selling methods | 0.06 (0.06) | 0.08 (0.08) | 0.01 (0.09) |

| Others’ responsibility →Sustainable consumer shopping | −0.01 (0.06) | −0.04 (0.09) | 0.04 (0.06) |

| Others’ responsibility →Sustainable consumption | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.02 (0.03) | −0.02 (0.03) |

| Economic considerations →Sustainable production methods | 0.09 (0.06) | 0.13 (0.08) | −0.04 (0.08) |

| Economic considerations →Sustainable selling methods | −0.06 (0.06) | 0.05 (0.08) | −0.15 (0.09) |

| Economic considerations →Sustainable consumer shopping | 0.05 (0.06) | 0.02 (0.09) | 0.18b (0.06) |

| Economic considerations →Sustainable consumption | −0.01 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.03) | −0.01 (0.03) |

| Ethical considerations →Sustainable production methods | 0.11 (0.06) | 0.09 (0.09) | 0.16b (0.06) |

| Ethical considerations Sustainable selling methods | 0.05 (0.06) | 0.08 (0.08) | 0.02 (0.09) |

| Ethical considerations →Sustainable consumer shopping | 0.04 (0.06) | −0.02 (0.10) | 0.12 (0.06) |

| Ethical considerations →Sustainable consumption | −0.02 (0.02) | −0.01 (0.03) | −0.03 (0.03) |

| Consumer motivation →Sustainable production methods | 0.01 (0.06) | 0.10 (0.08) | −0.07 (0.08) |

| Consumer motivation →Sustainable selling methods | 0.12b (0.06) | 0.05 (0.08) | 0.20b (0.09) |

| Consumer motivation →Sustainable consumer shopping | 0.11b (0.06) | 0.16b (0.09) | 0.06 (0.06) |

| Consumer motivation →Sustainable consumption | 0.75a (0.02) | 0.75a (0.03) | 0.76a (0.03) |

Several significant relationships between frame content and implications were detected in the study. The frame content ‘consumers’ responsibility’ was positively related to the implication ‘sustainable consumer shopping’ (β = 0.24, p < 0.01), while the frame content ‘others’ responsibility’ was positively related to ‘sustainable production methods’ (β = 0.32, p < 0.01). Furthermore, the frame content ‘consumer motivation’ had positive relationships with the frame implications ‘sustainable selling methods’ (β = 0.12, p = 0.04), ‘sustainable consumer shopping’ (β = 0.11, p = 0.05) and ‘sustainable consumption’ (β = 0.75, p < 0.01).

Results Pertaining to RQ2: Moderating Effects

The moderating effects of journalists’ gender were examined using multiple-group latent variable structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis (Table II). Several moderating effects were observed in this study. The relationship between ‘consumers’ responsibility’ and ‘sustainable consumer shopping was positive for male journalists (β = 0.41, p < 0.01) and non-significant for female journalists (β = 0.01, p = 0.93). To test the differences between the coefficients, their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated. If the confidence intervals overlap by less than 50%, the coefficients can be considered significantly different from each other (p < 0.05) (Cumming, 2009). This criterion suggests that the coefficients were significantly different: male journalists: 95% CI [0.23, 0.59]; female journalists: 95% CI [−0.11, 0.13]. Also, the relationship between ‘consumers’ responsibility’ and ‘sustainable consumption’ was non-significant for male journalists (β = −0.03, p = 0.37) and significant for female journalists (β = −0.06, p = 0.05); although the coefficients were not significantly different based on the 95% CI criterion; male journalists: 95% CI [−0.09, 0.03]; female journalists: 95% CI [−0.12, −0.01].

‘Economic considerations’ had a positive influence on ‘sustainable consumer shopping’ for female journalists (β = 0.18, p = 0.03), whereas this effect was non-significant for male journalists (β = 0.02, p = 0.85). Calculations of 95% CI (male journalists: 95% CI [−0.15, 0.19]; female journalists: 95% CI [0.06, 0.30]) suggested that the coefficients were significantly different. Also, the influence of ‘ethical considerations’ on ‘sustainable production methods’ was higher for female journalists (β = 0.16, p = 0.05) than for male journalists (β = 0.09, p = 0.41); although the difference between coefficients was not significant (male journalists: 95% CI [−0.09, 0.26]; female journalists: 95% CI [0.04, 0.28]).

Furthermore, the relationship between ‘consumer motivation’ and ‘sustainable selling methods’ was significantly higher for female journalists (β = 0.20, p = 0.02) than for male journalists (β = 0.05, p = 0.55) (male journalists: 95% CI [−0.09, 0.19]; female journalists: 95% CI [0.08, 0.32]). Also, ‘consumer motivation’ was positively related to ‘sustainable consumer shopping’ for male journalists (β = 0.16, p = 0.04) and non-significant for female journalist (β = 0.06, p = 0.45); although the difference between coefficients was not significant (male journalists: 95% CI [0.01, 0.34]; female journalists: 95% CI [−0.06, 0.18]). Finally, ‘consumer motivation’ was positively related to ‘sustainable consumption’ for both male journalists (β = 0.75, p < 0.01) and female journalist (β = 0.76, p < 0.01); with no significant difference between the coefficients (male journalists: 95% CI [0.69, 0.81]; female journalists: 95% CI [0.70, 0.82]).

Discussion

Based on the societal challenge of ‘consumer food sustainability, this study suggests that media framing should not be viewed independently of journalists’ gender. This indicates that media framing should not be regarded as a neutral and unbiased process. In this respect, our study represents an extension of social role theory, as it suggests that the social construction of gender roles can also be applied to how societal challenges and their implications are presented in the media. In particular, this study shows the relevance of media framing theory as a theoretical basis for the expanded understanding of gender-specific influences on the agenda-setting function of the media. This holistic approach provides a more nuanced understanding of how certain discourses about societal challenges arise and how they might be addressed.

Media agenda-setting theory and media framing theory together suggest that the media may influence the public’s opinion of certain subject areas, such as food and sustainability, by framing them in different ways. This study adds a new dimension by showing that the gender of journalists can influence which aspects of sustainability are highlighted as implications of underlying content. The results suggest that female journalists are more likely to emphasize economic considerations as drivers of sustainable consumer shopping, whereas male journalists are more focused on consumers’ responsibility and motivations as drivers of that frame implication. Similarly, female journalists showed a negative association between consumer responsibility and sustainable consumption.

These gender differences can also be viewed as reflections of broader societal gender norms. Female journalists’ focus on economic consequences is thus consistent with traditional gender roles, which see women as being particularly interested in care and community (e.g., Townsendet al., 2024), aligning with focusing on concerns such as everyday affordability and financial impacts of food shopping. Conversely, male journalists’ focus on the responsibility and motivational aspects of sustainable consumer shopping may reflect the traditional male roles associated with individual performance-oriented goals.

Interestingly, while both male and female journalists strongly associated consumer motivation with sustainable consumption, the pathways through which they framed the other implications diverged. For example, female journalists demonstrated a significant association between ethical considerations and sustainable production methods, whereas this relationship was not significant for male journalists. This may reflect a broader orientation toward care, ethics, and social responsibility, consistent with gender socialization theory and traditional female roles, and might even extend to gender ideology issues, which refer to the attitudes that individuals hold regarding the division of family responsibilities in couples (Bornatici & Zinn, 2025). This means that gender socialization may affect journalists’ professional behavior. The findings highlight the need for broad gender representation in journalism to ensure balanced and inclusive media coverage. For example, the frequent underrepresentation of women in news coverage of societal issues (e.g., Santoniccoloet al., 2023) may skew the presentation of our societal challenges and what implications can be considered.

Based on the results of this study, we encourage media organizations to be aware of the potential gender bias that may arise in journalistic articles on societal issues, such as consumer food sustainability. Media organizations could, for example, offer further training to their journalists to ensure balanced and inclusive coverage of food sustainability issues. By working on these issues, media organizations will be able to implement continuing education programs that specifically focus on creating awareness of the possible gender bias that could arise in connection with journalistic reporting. Media organizations may also wish to pay particular attention to the gender bias that may arise in connection with the consistent unequal gender representation of journalists in news stories.

The results of this study highlight several societal challenges. One of these challenges is the perpetuation of gender stereotypes in media coverage. If male and female journalists highlight different aspects of food sustainability and the possible implications related to it, this may ultimately contribute to the maintenance of traditional gender roles in society. This may limit the diversity of perspectives and reduce the comprehensive and inclusive understanding of sustainability issues. This is also important because the way various issues are highlighted in the media may contribute to shaping how the public understands and engages with sustainability agendas. For example, if economic or ethical aspects are only highlighted by female journalists, this may lead to excessive emphasis on consumer motivation considerations at the expense of economic or ethical dimensions.

Public authorities may seek to mitigate gender bias by adopting a multifaceted approach to their communication on consumer food sustainability issues, addressing both the content and delivery of messages, and incorporating different genders, backgrounds, and perspectives in the development of communication materials. This allows the content to reflect a wider range of views on food and sustainability, making the area more inclusive and relatable to a wider audience. In this respect, ongoing monitoring and evaluation of communication efforts are important for identifying and addressing emerging gender biases. This involves regularly reviewing content, gathering feedback from diverse audiences, and making adjustments, as needed.

Conclusion

The study shows that the gender of journalists has a significant influence on how sustainability in consumer food is portrayed in the Danish media. Articles written by female journalists tend to emphasize economic and ethical aspects, while male journalists focus more on consumer responsibility and motivation. This suggests that media framing is not a neutral process, but is influenced by societal gender norms. By combining media framing theory with theories of gender socialization and social roles, the study points to the need for greater diversity in journalism. When gender plays a role in which frames and consequences are highlighted, it may influence the public understanding of food sustainability. Therefore, media organizations should consider introducing editorial guidelines and continuing education that strengthen awareness of gender bias and promote a more inclusive approach to journalistic coverage.

Limitations and Future Research

In this study, we used quantitative media content analysis to investigate potential gender bias in media representations of consumer food sustainability. Similar to other studies, this research has a number of challenges and limitations that may guide future studies on media and gender bias. First, we used a quantitative methodology that focuses on identifying and measuring various relationships between frame contents and implications, without specifically considering possible qualitative aspects (e.g., journalists’ personal beliefs, their own experiences with gender issues, etc.) that may influence these relationships. Thus, combining both qualitative and quantitative approaches by integrating a mixed-methodology approach may provide more nuanced details of the study outcomes. Furthermore, incorporating qualitative data analyses could offer improved explanations of the observed direct and moderating effects. Second, we concentrated on written types of communication, specifically newspaper articles, excluding other communication forms such as social media platforms, digital outlets including blogs and websites, and television, which may also influence the framing of consumer food sustainability issues. Hence, the expansion of future content studies to cover these media could lead to more comprehensive data, which may further increase the conclusiveness of the findings. Third, in this study, journalists were classified as male or female based on their names, following a binary classification. This approach was chosen for practical and statistical reasons, enabling clear operationalization of gender as a moderating variable. However, we acknowledge that this binary framework does not capture the full spectrum of gender identities, including non-binary and transgender individuals. While the proportion of non-binary individuals in Denmark is relatively low (DIHR - Danish Institute for Human Rights, 2025), future research may wish to consider more inclusive gender categorizations to better reflect the diversity of journalistic voices.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

References

-

Bellotti, E., & Panzone, L. (2016). Media effects on sustainable food consumption: How newspaper coverage relates to supermarket expenditures. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 40(2), 186–200.

Google Scholar

1

-

Béné, C., & Abdulai, A.-R. (2024). Navigating the politics and processes of food systems transformation: Guidance from a holistic framework. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 8, 1399024. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2024.1399024.

Google Scholar

2

-

Bengtsson, M., Alfredsson, E., Cohen, M., Lorek, S., & Schroeder, P. (2018). Transforming systems of consumption and production for achieving the sustainable development goals: Moving beyond efficiency. Sustainability Science, 13(6), 1533–1547.

Google Scholar

3

-

Berglund, T., & Gericke, N. (2016). Separated and integrated perspectives on environmental, economic, and social dimensions: An investigation of student views on sustainable development. Environmental Education Research, 22(8), 1115–1138.

Google Scholar

4

-

Bornatici, C., & Zinn, I. (2025). Beyond tradition? How gender ideology impacts employment and family arrangements in Swiss couples. Gender & Society, 39(2), 285–320.

Google Scholar

5

-

Buturoiu, R., Corbu, N., & Boțan, M. (2023). Agenda setting: 50 years of research. In R. Buturoiu, N. Corbu, M. Botan (Eds.), Patterns of news consumption in a high-choice media environment (pp. 11–30), Springer.

Google Scholar

6

-

Conrad, Z., & Blackstone, N. T. (2021). Identifying the links between consumer food waste, nutrition, and environmental sustainability: A narrative review. Nutrition Reviews, 79(3), 301–314.

Google Scholar

7

-

Crosby, T., Astone, J., & Raimond, R. (2021). Investing in the true value of sustainable food systems. In True Cost Accounting for Food (pp. 221–231), Routledge.

Google Scholar

8

-

Cumming, G. (2009). Inference by eye: Reading the overlap of independent confidence intervals. Statistics in Medicine, 28(2), 205–220.

Google Scholar

9

-

Davidson, N. R., & Greene, C. S. (2024). Analysis of science journalism reveals gender and regional disparities in coverage. eLife, 12(P84855), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.84855.

Google Scholar

10

-

DIHR - Danish Institute for Human Rights (2025). LGBT+ – What and how many? The Danish Institute for Human Rights. Retrieved May 12, 2025. http://www.humanrights.dk/lgbtbarometer/what-and-how-many.

Google Scholar

11

-

Dirikx, A., & Gelders, D. (2010). To frame is to explain: A deductive frame-analysis of Dutch and French climate change coverage during the annual UN Conferences of the Parties. Public Understanding of Science, 19(6), 732–742.

Google Scholar

12

-

DLA Piper. (2024). Making sustainability sustainable in the consumer goods, food and retail sector. DLA Piper. Retrieved May 4, 2025. https://www.dlapiper.com/en/insights/publications/2024/09/making-sustainability.

Google Scholar

13

-

Donner, M., Mamès, M., & de Vries, H. (2024). Towards sustainable food systems: A review of governance models and an innovative conceptual framework. Discover Sustainability, 5(1), 414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-000414-x.

Google Scholar

14

-

Döring, T. F., Vieweger, A., Pautasso, M. A., Vaarst, M., Finckh, M. R., & Wolfe, M. S. (2015). Resilience as a universal criterion of health. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 95(3), 455–465.

Google Scholar

15

-

Elo, S., Kääriäinen, M., Kanste, O., Pölkki, T., Utriainen, K., & Kyngäs, H. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open, 4(1), 1–10.

Google Scholar

16

-

Entman, R. M. (2004). Projects of power: Framing news, public opinion, and U.S. foreign policy. University of Chicago Press.

Google Scholar

17

-

Evans, D., Welch, D., & Swaffield, J. (2017). Constructing and mobilizing ‘the consumer’: Responsibility, consumption and the politics of sustainability. Environment and Planning A, 49(6), 1396–1412.

Google Scholar

18

-

FAO (2018). Sustainable Food Systems, Concept and Framework. http://www.fao.org/3/ca2079en/ca2079en.pdf.

Google Scholar

19

-

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Google Scholar

20

-

Garnett, T. (2013). Food sustainability: Problems, perspectives and solutions. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 72(1), 29–39.

Google Scholar

21

-

Geschke, D., Sassenberg, K., Ruhrmann, G., & Sommer, D. (2010). Effects of linguistic abstractness in the mass media: How newspaper articles shape readers’ attitudes toward migrants. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications, 22(3), 99–104.

Google Scholar

22

-

Giesen, R. van, & Leenheer, J. (2019). Towards more interactive and sustainable food retailing: An empirical case study of the supermarket of the future. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 47(1), 55–75.

Google Scholar

23

-

GlobalData. (2020). Covid-19 hasn’t dented consumer interest in sustainability. Just Food. https://www.just-food.com/comment/covid-19-hasnt-dented-consumer-interest-insustainability/.

Google Scholar

24

-

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. New York: Harper & Row.

Google Scholar

25

-

Gollnhofer, J. F., Weijo, H. A., & Schouten, J. W. (2019). Consumer movements and value regimes: Fighting food waste in Germany by building alternative object pathways. Journal of Consumer Research, 46(3), 460–482.

Google Scholar

26

-

Goyanes, M., & Cañedo, A. (2024). Media Influence on Opinion Change and Democracy. Springer Nature Switzerland.

Google Scholar

27

-

Hansen, T. (2020). Media framing of copenhagen tourism: A new approach to public opinion about tourists. Annals of Tourism Research, 84(9), 1–13.

Google Scholar

28

-

Hansen, T. (2022). Consumer food sustainability before and during the Covid-19 crisis: A quantitative content analysis and food policy implications. Food Policy, 107, 102207.

Google Scholar

29

-

HealthFocus International. (2020). The changing world of nutrition and wellness amidst the COVID 19 pandemic. https://www.healthfocus.com/lpage/the-changing-world-of-nutrition-andwellness-amidst-the-covid-19-pandemic/.

Google Scholar

30

-

Jamil, S., Çoban, B., Ataman, B., & Appiah-Adjei, G. E. (Eds.), (2020). Handbook of Research on Discrimination, Gender Disparity, and Safety Risks in Journalism. IGI Global.

Google Scholar

31

-

Katzeff, C., Milestad, R., Zapico, J. L., & Bohné, U. (2020). Encouraging organic food consumption through visualization of personal shopping data. Sustainability, 12(9), 3599.

Google Scholar

32

-

Kemalbay, G., & Korkmazoğlu, Ö.B. (2014). Categorical principal component logistic regression: A case study for housing loan approval. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 109, 730–736.

Google Scholar

33

-

Kidwell, B., Farmer, A., & Hardesty, D. M. (2013). Getting liberals and conservatives to go green: Political ideology and congruent appeals. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(2), 350–367.

Google Scholar

34

-

Kingdon, J. W. (1995). Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. New York: HarperCollins College Publishers.

Google Scholar

35

-

Kline, S. L., Karel, A. I., & Chatterjee, K. (2006). Covering adoption: General depictions in broadcast news. Family Relations, 55(4), 487–498.

Google Scholar

36

-

Komarovsky, M. (1992). The concept of social role revisited. Gender & Society, 6(2), 301–313.

Google Scholar

37

-

Kouchaki, M., & Kray, L. J. (2018). I won’t let you down: Personal ethical lapses arising from women’s advocating for others. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 147, 147–157.

Google Scholar

38

-

Lammers, P., Ullmann, L. M., & Fiebelkorn, F. (2019). Acceptance of insects as food in Germany: Is it about sensation seeking, sustainability consciousness, or food disgust? Food Quality and Preference, 77, 78–88.

Google Scholar

39

-

Liu, X., Li, S., Chen, W., Yuan, H., Ma, Y., Siddiqui, M. A., & Iqbal, A. (2023). Assessing greenhouse gas emissions and energy efficiency of four treatment methods for sustainable food waste management. Recycling, 8(5), 66.

Google Scholar

40

-

McCombs, M. E. (2004). Setting the Agenda: The Mass Media and Public Opinion. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Google Scholar

41

-

Mešić, A., Jurić, M., Donsì, F., Maslov Bandić, L., & Jurić, S. (2024). Advancing climate resilience: Technological innovations in plant-based, alternative and sustainable food production systems. Discover Sustainability, 5, 423.

Google Scholar

42

-

Messner, R., Richards, C., & Johnson, H. (2020). The ‘Prevention Paradox’: Food waste prevention and the quandary of systemic surplus production. Agriculture and Human Values, 37(3), 805–817.

Google Scholar

43

-

Mouchtaropoulou, E., Mallidis, I., Giannaki, M., Koukaras, K., Früh, S., Ettinger, T., Benmehaia, A. M., Kacem, A., Achour, L., Detzel, A., Gianotti, A., Samoggia, A., Ayfantopoulou, G., Argiriou, A. (2024). Consumer willingness to pay for fair and sustainable foods: Who profits in the agri-food chain? Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 8, 1504985.

Google Scholar

44

-

Naser, A. (2020). Relevance and challenges of the agenda-setting theory in the changed media landscape. American Communication Journal, 22(1), 1–15.

Google Scholar

45

-

Nichifor, B., Zaiț, L., & Timiras, L. (2025). Drivers, barriers, and innovations in sustainable food consumption: A systematic literature review. Sustainability, 17(5), 2233.

Google Scholar

46

-

Noble, S. M., Griffith, D. A., & Adjei, M. T. (2006). Drivers of local merchant loyalty: Understanding the influence of gender and shopping motives. Journal of Retailing, 82(3), 177–188.

Google Scholar

47

-

North, L. (2016). The gender of ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ news. Journalism Studies, 17(3), 356–373.

Google Scholar

48

-

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). An overview of psychological measurement. In B. B. Wolman (Ed.), Clinical diagnosis of mental disorders: A handbook (pp. 97–146). Springer.

Google Scholar

49

-

Paveglio, T., Norton, T., & Carroll, M. S. (2011). Fanning the flames? Media coverage during wildfire events and its relation to broader societal understandings of the hazard. Human Ecology Review, 18(1), 41–52.

Google Scholar

50

-

Poore, J., & Nemecek, T. (2018). Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science, 360(6392), 987–992.

Google Scholar

51

-

Principato, L., Mattia, G., Di Leo, A., & Pratesi, C. A. (2021). The household wasteful behaviour framework: A systematic review of consumer food waste. Industrial Marketing Management, 93, 641–649.

Google Scholar

52

-

Reppmann, M., Harms, S., Edinger-Schons, L. M., & Foege, J. N. (2024). Activating the sustainable consumer: The role of customer involvement in corporate sustainability. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 53, 310–340.

Google Scholar

53

-

Ruoho, I., & Torkkola, S. (2018). Journalism and gender: Toward a multidimensional approach. Nordicom Review, 39(1), 67–79.

Google Scholar

54

-

Santoniccolo, F., Trombetta, T., Paradiso, M. N., & Rollè, L. (2023). Gender and media representations: A review of the literature on gender stereotypes, objectification and sexualization. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(10), 5770.

Google Scholar

55

-

Semetko, H. A., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2000). Framing European politics: A content analysis of press and television news. Journal of Communication, 50(2), 93–109.

Google Scholar

56

-

Serhan, H., & Yannou-Lebris, G. (2020). The engineering of food with sustainable development goals: Policies, curriculums, business models, and practices. International Journal of Sustainable Engineering, 14(1), 12–25.

Google Scholar

57

-

Smith, M. D., & Floro, M. S. (2020). Food insecurity, gender, and international migration in low- and middle-income countries. Food Policy, 91, 101837.

Google Scholar

58

-

Sonck-Rautio, K., Tynkkynen, N., & Lahtinen, T. (2025). Addressing consumer perspectives on sustainable food packaging: Insights from the research literature. In N. Tynkkynen, et al. (Eds.), Sustainability in food packaging (pp. 101–142). Cham: Springer.

Google Scholar

59

-

Spinde, T., Jeggle, C., Haupt, M., Gaissmaier, W., & Giese, H. (2022). How do we raise media bias awareness effectively? Effects of visualizations to communicate bias. PLOS ONE, 17(4), e0266204.

Google Scholar

60

-

Steiner, L. (2012). Failed theories: Explaining gender difference in journalism. Review of Communication, 12(3), 201–223.

Google Scholar

61

-

Stanziani, M., Cox, J., MacNeil, E., & Carden, K. (2024). Implicit gender role theory, gender system justification, and voting behavior: A mixed-method study. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 21(3), 1151–1170.

Google Scholar

62

-

Thompson, M., Carlson, D., Crawford, W., Kacmar, K. M., & Weaver, S. (2022). You make me sick: Abuse at work and healthcare utilization. Human Performance, 35, 193–217.

Google Scholar

63

-

Townsend, C. H., Kray, L. J., & Russell, A. G. (2024). Holding the belief that gender roles can change reduces women’s work-family conflict. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 50(11), 1613–1632.

Google Scholar

64

-

Van der Pas, D. J., & Aaldering, L. (2020). Gender differences in political media coverage: A meta analysis. Journal of Communication, 70(1), 114–143.

Google Scholar

65

-

Venkatesh, V., & Morris, M. G. (2000). Why don’t men ever stop to ask for directions? Gender, social influence, and their role in technology acceptance and usage behavior. MIS Quarterly, 24, 115–139.

Google Scholar

66